The Incident

My introduction to the real world of cybersecurity was a brief crash-course in incident response and threat intel. During my second term in a college cybersecurity program, some malware had infected the online learning portal and initial attempts to bring it to their attention went ignored. Within a year, an internship provided me with the tools to help the college remediate the threat. But during that time a malicious browser extension known as LNKR was having its way with student computers.

For many freshmen, starting college is a challenging experience regardless of age. New environments, new social hierarchy, new responsibilities, and not much help to find their way along. Success requires the skill to adjust quickly. In theory, the transition should be easier for students who’ve had the time to grow into adulthood.

For older students who’ve been insulated from the evolution of remote learning technology, the environment can seem a bit chaotic at first. The experience can be much like that of the freshman experience, replacing the crippling hangovers with the dread of crippling financial burden. At least, that’s what it was like for me when I decided to go back to college to get a degree in “Cybersecurity”.

After 11 years, the online college experience had changed considerably. I had taken a few online courses before, but those paled in comparison to what’s now available. Streaming video content, interactive virtual learning environments, and communication platforms are some of the standout features that support the modern learning experience.

For me, this new ecosystem was made even more arduous by my newfound paranoia, instilled in me through two years of binging cybersecurity podcasts leading up to starting the program. Shortly before I my first term I bought a new computer and downloaded some antivirus software. An overabundance of caution was going to be my daily mantra. Gone were the days of P2P file sharing. Gone were the days of downloading songs for a penny from mysterious Russian websites. This was a new computer, a new email address, new passwords, and a new network connection. This was a completely new online identity. So imagine my shock when I received my first AV alert.

It was disappointing at first. I thought I was being overly cautious. No one in my trusted circle even touches my computer, so in my novice experience this was obviously the result of something I had done. But after a few scans from my antivirus came back clean, I realized this may not be the case.

My college uses a popular e-learning platform called Blackboard. It allows instructors to publish learning materials, upload supplemental content, create exams, and communicate with students. They all have writable privileges to this product and it can be hosted locally or remotely just like WordPress or other popular blog platforms. Students have “read only” privileges but faculty have the ability to modify and post new content.

I looked a little deeper at the alert messages, making note of when and where I was on the site when I received them. This helped narrow down the actions that were triggering them. After some experimenting, I finally realized that every time I clicked on a specific class page, I would then receive the alert.

The alert message told me that my course webpage was trying to redirect me to a malicious domain called programdiag[.]com. A quick preliminary search for this domain name in Google didn’t turn up much. Mind you, this was two months into my education so I had very little well-of-knowledge to draw on. What was available was basically unintelligible from a technical standpoint. The alerts continued throughout the term and after a while I started ignoring them.

During my second term, I was taking a different class from the same professor and encountered the same problem. Every time I clicked on the link to the course content I received an alert for the same malicious domain. I decided it was time to contact my professor and explain what was happening. Unfortunately, he told theorized that what I was experiencing was likely the byproduct of overly sensitive antivirus software. Just in case, he directed me to our college’s IT department… who theorized the problem was coming from my machine and that I should install an antivirus program and decontaminate my machine. So much for trying to be helpful.

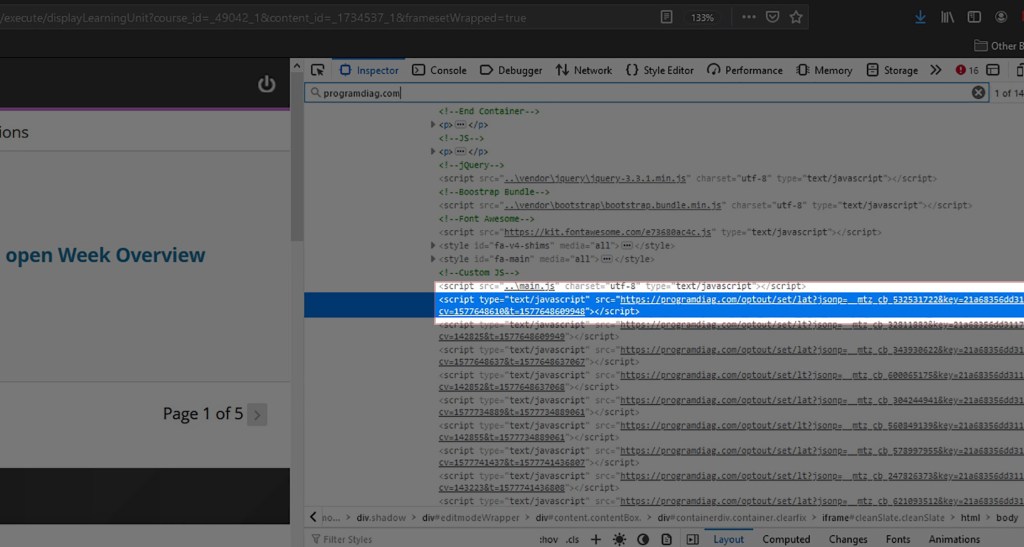

I was left feeling a little foolish and more than frustrated due to the constant alerts I was receiving every time I visited my course site. I was convinced that the problem wasn’t resonating from my computer at all but had infected the school’s side of the platform. If I was to get anyone to hear me out I was going to have to bring them some evidence. I started by inspecting the HTML of the course homepage. A quick search for “programdiag[.]com” within the contents turned up some embedded Javascript within the HTML header. I highlighted it, took a screenshot, and saved it for later (pictured below). The alerts continued.

In my third term, I enrolled in a class being taught by a different professor and immediately began encountering the same alerts. After reading the syllabus I noticed that this course page had materials signed by a different instructor. This suggested that different instructors were teaching specific classes in rotation each term. It seemed possible that instead of creating new homepages for these courses they were reusing them and handing off privileges.

It was during this time I started at my internship with the Shadowserver Foundation. One day, I brought my problem to my mentor and together we looked into the details. We started with a Whois Lookup and found the domain had been registered anonymously within the last two years. (I learned this is a red flag.) We then looked up the suspicious domain name in VirusTotal and found it to be flagged as malicious. After showing me the ropes at Shadowserver, he encouraged me to continue my hunt which started me on the path to my first deep dive.

A year passed since my first fledgling look into the programdiag domain name. By this time a lot of progress had been made by the malware research community and a new search on the domain turned up the first informative articles. According to Netskope this domain was part of a campaign attributed to an adware called LNKR. Further searches on LNKR revealed that Chris Krebs published an article a few years prior, however programdiag wasn’t a part of that campaign. I was cooking with fire.

What I found is that LNKR had at least two recognizable campaigns with two very distinct methods of infection. I also discovered that LNKR isn’t just adware, but also performs a significant amount of reconnaissance and is often used in conjunction with other malware as a part of a “suite”. The following deep dive compiles the intel I found into one encompassing report.

Overview

The LNKR trojan is an infected browser extension that monitors the web pages visited by the user, looking for pages with administrative privileges such as blog sites or web-based virtual learning environments. When a user with admin privileges posts to the page, the extension will include a stored cross-site scripting attack and injects malicious JavaScript into the legitimate HTML of the page. This is used to redirect the second-party visitors of the site to both benign and malicious domains. It is most commonly known to infect these visitors with adware that can additionally performs reconnaissance on host systems.

About the Developers

Operations originate from a shell company registered in Hong Kong known as Brocode. However, several sources state that some of the earliest artifacts found point to operations being based in Eastern Europe, possibly Ukraine or Russia. One of the early C2 domain names (lnkr[.]us) was registered to a Sergei Filov.

A screenshot of the brocodeltd.com website describing some of their analytic and reconaissance capabilities.

Primary Infection Vector

The operatives behind LNKR were first observed infecting Flash plug-ins and and legitimate browser extensions available in the Google Chrome Store. These extensions containing malicious code will search each web page visited by the user for writable permissions such those provided by blogs like WordPress, or online learning portals hosted by educational institutions such as Blackboard and D2L.

Secondary Infection Vector

The second stage begins when LNKR finds a web page as described above. When an authenticated user commits a POST request to the website, the malicious browser extension will then inject the script into the HTML header of the page. When a secondary victim visits the infected web page, the embedded JavaScript redirects the browser to a domain within the LNKR network. This redirect acts as the primary source of distribution for the LNKR malware as it begins to fan out to other systems. This payload is used to leverage adware, perform reconnaissance, and redirect the victim’s browser to both benign and malicious domains.

A screenshot of the malicious JavaScript that has been injected into the HTML of a college’s Blackboard web page. Programdiag[.]com is a domain name known to be associated with the LNKR malware.

Changes To The Primary Infection Vector

At the time of this writing, the threat actors behind the current LNKR campaign are perceived to be in an active state of development of primary infection techniques. Google Chrome Store administrators began removing infected extensions as they became aware of them and changes in Google’s policy have made it much more difficult to compromise legitimate browser extensions. This has likely forced the threat actors to develop new methods of distribution. On May 23, 2021 Trend Micro published a white-paper reporting on a new infection vector of the LNKR malware.

This new campaign begins when a user visits a warez website for the purpose of downloading cracked software. The “Download” link for the desired software triggers a series of redirects to malicious domains. The first of which begins to download the primary payload known as CopperStealer instead. These redirects are most often implemented in PHP and can lead to further installs of additional malware.

The main function of CopperStealer is credential theft, which primarily targets Facebook and Google assets. It is also now the preferred method for automatically installing the malicious browser plug-in LNKR. This new distribution method ensures that LNKR is no longer limited to Google Chrome and can infect Firefox, Opera, Microsoft Edge, Internet Explorer, Baidu, and Yandex.

In addition to CopperStealer, those behind the most recent incarnation of the LNKR campaign have also begun incorporating other malware such as SmokeLoader, CoinHive, and PoisonIvy.

In Closing

Oddly, no other students reported any problems to faculty or administration. However, when I inquired about the AV popups in our student cybersecurity Discord server, most knew what I was talking about. It’s just that no one did anything about it. I’ll let you draw your own conclusions on that one.

When I finished my report I sent the evidence to the IT department, all 277 pages (including IOC’s). After a year of uninterrupted infection it had become a significant problem. After I shared my report, I reached out to the professor whose computer had originated the LNKR infection. According to him, he had to manually delete every instance of malicious JavaScript from every course page that he had ever created. Because edits were made to these homepages so often, LNKR had injected hundreds of lines of JavaScript. Making matters worse, the course pages were shared among the instructors causing the problem to mushroom exponentially.

References

https://www.netskope.com/blog/lnkr-makes-a-comeback-this-ads-for-us

https://github.com/Zenexer/lnkr

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2020/03/the-case-for-limiting-your-browser-extensions/

https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/21/c/websites-hosting-cracks-spread-malware-adware.html?utm_source=trendmicroresearch&utm_medium=smk&utm_campaign=0321_Adware

https://documents.trendmicro.com/assets/pdf/appendix-IoCs-websites-hosting-cracks-spread-malware-adware.pdf

https://securitytrails.com/blog/lnkr-malicious-browser-extension

https://www.reddit.com/r/Malware/comments/4cw9fz/lnkrus_redirect_malware_report/

https://twitter.com/malwrhunterteam/status/1253662725219254275

LNKR_webarch_062021.zip

Interesting and thank you for sharing your LNKR journey.

This sentence resonated with me

“Oddly, no other students reported any problems to faculty or administration. However, when I inquired about the AV popups in our student cybersecurity Discord server, most knew what I was talking about. ”

I have seen a phishing e-mail being sent to 55 people where it was obvious it was to trigger people into downloading malware and only 1 reported it.

about your paranoia: also recognizable when I started my infosec career in 2001.

“even paranoids have real enemies”

LikeLike