Abstract

The role of a digital forensic investigator is to demystify the essential details of cybercrime. As complex as the process may seem, it is as simple as providing factual answers to the 5Ws (who, what, where, when, why… and of course how). But, the lingering question of “who” can carry the most consequence, and is often the hardest to answer. Attributing a cyber attack to a government entity or its citizens can be an accusation of the violation of international law. Yet, the decisions surrounding attribution can be clouded by prejudice, sensationalism, and political motive. This scientific negligence can have severe implications in the delicate world of global politics. The integrity of the investigative process remains intact by using empirical analysis to identify and track the actions of cybercriminals.

Cyber Conflict in the Middle East

In November 2012, researchers with Norman ASA observed a year-long surveillance campaign targeting both Israeli and Palestinian government entities. The campaign began with spear-phishing emails involving topics on tensions in the Middle East. These targeted emails contained a malicious attachment that infected the victim’s computer with the commercially available remote access trojan (RAT) called XtremeRat. Initial IP addresses belonging to the command-and-control (C2) structure used to facilitate the transfer of information between the attackers and the infected computers resolved to hosting services within the United States. Upon further analysis, it was discovered that older versions of the malware had been communicating with this C2 since October 2011. (Fagerland, 2012)

By the Spring of 2012, almost all domains used in this campaign had changed to resolve to IP addresses within the range of 188.161.*. These hosts belonged to a provider identified as “Palestinian Territory, Occupied Gaza Palestine Telecommunications Company (Paltel), ASN: AS12975”, based in Ramallah, West Bank. Other IP addresses resolved to domains belonging to the provider identified as “Palestinian Territory, Occupied Gaza Hadara Technologies Private Shareholding Company, ASN: AS15975”. (Fagerland, 2012)

The group that would become known as TA 402 has consistently engaged in espionage in the Middle East and North African (MENA) region. Their tradecraft has been documented under other monikers such as Molerats, Gaza Hacker Team, and Gaza CyberGang. Over the years, TA 402 has evolved its methods to include a constantly changing toolset of C2 infrastructure and malware.

Until 2015, TA 402 relied heavily on publicly available malware commonly used by a variety of cybercriminals across the globe. But then, the first significant signs of evolution in the group’s abilities began to take shape. A custom malware family known as NeD Worm (aka DustySky) was developed and TA 402 began to expand its operations to target entities within Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Egypt, Europe, and the United States. (Clearsky Research Team, 2016)

The sophistication of these attacks continued to evolve. As of writing, TA 402 has expanded t include targets in the energy and defense industries, various military institutions, journalists, and software developers in Palestine, Israel, the United States, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Egypt, Libya, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Oman, Yemen, Syria, UAE, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Lebanon. TA 402 directly engaged Digital Forensics and Incident Response (DFIR) teams involved with investigating the very attacks they were responsible for.

The Problem with Palestine

Sometime in 2012, various media outlets and research groups began referring to TA 402 as a Palestinian-sponsored threat actor. Some researchers have pointed to the fact that the C2 infrastructure involved in some of the earliest attacks executed by TA 402 resides on servers based in the West Bank. However, the nature of the region’s geopolitics prohibits Palestine from exercising sovereignty over any internet infrastructure within its territory. The servers in question don’t belong to any Palestinian entities. As Fabio Cristiano states,

“With Israel in full control of internet infrastructural networks – in East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza – Palestinians only have access to a “second-hand” connectivity service. Palestinian internet service providers (ISPs), in fact, depend on Israeli ISPs to supply internet connection across the territory. ” (2021)

Assigning attribution based on ambiguous forensic evidence is ethically problematic.

Between 2016 to 2018, the World Bank observed that illegal blockades imposed by Israeli authorities grew from restricting the import of information and communication technologies (ICT) to limiting the bandwidth, spectrum, and frequency allocation of Palestinian telecommunications. These measures have ensured that this infrastructure is indefinitely antiquated, making it an easy target for hackers to appropriate components of the network for use in criminal activities. (Cristiano, 2021 p 2 – 3) As Andy Greensberg points out, “Sophisticated hackers can route their connections through circuitous proxies and blind alleys, making it almost impossible to follow their tracks.” (2019, para. 21)

During the Arab Spring of 2011, Arab governments began searching all at once for ways to counter the uprisings. Many turned their attention to a variety of “off-the-shelf” malware that can be obtained for free on the internet or licensed as a part of a paid criminal service. For instance, the UAE began targeting dissidents with a “lawful intercept” spyware called Remote Control System (RCS), licensed by the Italian “security” company, Hacking Team. Security researcher Dr. William Marczak writes in his dissertation that this spyware was used to target a UAE activist named Ahmed Mansoor. After the RCS infection was eradicated, his computer was compromised again by the malware known as Xtreme RAT. (2016, p. 19-23)

Xtreme Rat is a remote access trojan used for espionage purposes. It allows the attacker to interact with the infected system through a user interface, upload and download files, manipulate the registry and running processes, take screenshots, and record audio and video on the victim’s machine. It has been a favorite for novice users due to its ease of use and that it is freely available on the internet.

Documenting further proof of the pollination of these malware families across the MENA region, Marczack notes, “In one leaked email from Hacking Team, the company’s Operations Manager says that the UAE client that hacked Mansoor also uses SpyNet and Xtreme RAT for some operations”. The XtremeRat malware has also been used in conjunction with the PoisonIvy, BlackShades, and DarkComet malware families in attacks committed against Syrian activists. (2016, p. 19-23) Upon further investigation, Marczak discovered that the domain name used to communicate with SpyNet was also used in another attack using the njRAT malware to target the relative of an unnamed activist. The use of njRAT and SpyNet overlaps with other Middle Eastern group activities around the same time.

The TA dubbed Arid Viper is also an active cybercrime group in the Middle East. Research published by Trend Micro stated:

“Arid Viper used leased command-and-control infrastructure based in Germany. Researchers at Trend Micro found that servers that received the stolen data were also used by other cyber-criminal campaigns that otherwise looked unrelated.” (Lemos 2015)

The same phenomenon can be seen again when cross-referencing C2 infrastructure attributed to TA 402.

In 2014, the security company FireEye released its research into TA 402’s usage of the Xtreme Rat malware. In the report, they published a list of fifteen domain names they called “The Uranio Cluster” which were used by XtremeRat for C2 communications. (Villeneuve & Bennet, 2014)

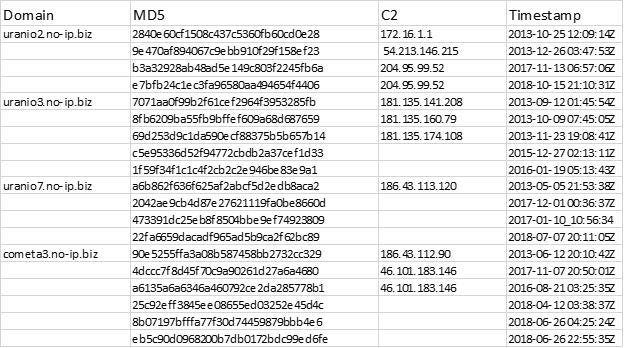

MD5 hashes representing different versions of the Xtreme Rat malware communicating with C2 domains belonging to the Uranio Cluster. Data provided courtesy of the Shadowserver Foundation 2022-11-19

Between October 2013 and October 2018 the domain uranio2.no-ip[.]biz resolved to three IP addresses: 54.213.146[.]215, 204.95.99[.]52, and 172.16.1[.]1. The IP address 204.95.99[.]52 currently resides on a server in Redmond, WA, and has been acting as a C2 for various forms of malware including DarkComet from at least July 2014 to July 2020. (Shadowserver, 2022) This means that the C2 used by TA 402 in 2012 to spy on Palestinian and Israeli targets overlaps with infrastructure belonging to the same malware family used to spy on Syrian dissidents. This insinuates a multi-purpose network used by various actors over an extended period.

The various campaigns in the MENA region between 2011 and 2014 show evidence of what may be a botnet-for-hire. Because much of the malware being used in the area at this time was freely available, the attackers would also need to procure access to a communication network that allowed them to upload files from, or download files to the victim’s device. The devices that make up these botnets are owned by a criminal third party who rents out its use to other criminals, often by the hour. Sometimes, a machine infected with the malware that comprises a part of the botnet can be patched the next day or it can remain infected indefinitely. Unless the attackers had access to their own C2 network, they would need to develop a partnership with someone who was in the business of renting one out.

In 2015, TA 402 launched what would become known as Operation Dusty Sky. This intelligence-gathering campaign differed from previous operations due to the implementation of a new custom malware family called NeD Worm. No other threat actor has access and it is considered exclusive to their operations. The IP address 107.191.47[.]42 that delivered NeD Worm to some of the victims in this campaign was a known C2 of the “Avalanche” criminal network. One year after Operation DustySky, the Shadowserver Foundation supported international Law Enforcement “in the coordinated takedown of the criminal-operated Avalanche malware delivery platform” created and maintained by Ukrainian-born Gennadiy Kapkanov who was later arrested in 2018. (Shadowserver, 2016) (USDOJ, 2019) The diversity of TA 402’s operations reveals how well they’ve been able to implement so many different pieces of the criminal internet.

Other evidence presented in the 2016 “Operation DustySky” report should be called into question. ClearSky researchers claimed that NeDWorm was developed exclusively for TA 402 by a Palestinian developer with ties to Hamas. Their support for this claim states, “Recent samples (of NedWorm) had “Last Saved By” properties of the document point to a specific individual who we believe is one of the attackers. In his Social[sic] media accounts this individual defines himself as a Software Engineer who lives in Gaza.” A simple Google search for “how to spoof a last saved by date” will provide the reader with enough information to accomplish this in a matter of minutes. Thus, the entire foundation for the Hamas attribution theory that is continuously perpetuated is built on a simple piece of “evidence” that can easily be faked.

Making a Statement

Consider the purpose of attribution. Ideally, this is done so that a governing body can exact an appropriate response. When a cybercrime is committed against the asset(s) of a sovereign country there are two types of responses: the soft power of diplomatic actions (acquiescence and strengthening cyber security, diplomatic protests, legal measures, and political & economic sanctions); and the hard power of non-diplomatic actions (retaliation in cyberspace, covert retaliation in cyberspace, military retaliation). (van der Meer, 2018, p. 3-6)

Acquiescence and defensive hardening involve “simply acknowledging that the cyber security measures, in this case, were not adequate… [and] the targeted networks have been improved and will receive more and continuing attention” (van der Meer, 2018, p.3) This is the only option that does not include the implication of and direct engagement with the suspected party. As you can see, the non-diplomatic options carry significant consequences.

Some of the most well-known examples of the use of diplomatic tools include actions taken by the United States of America against Russia. In 2016, the U.S. responded to the disruption of its presidential elections by expelling 35 Russian diplomats from the country. Four years later, the U.S. Department of Justice charged six Russian GRU officers “in Connection with Worldwide Deployment of Destructive Malware and Other Disruptive Actions in Cyberspace” (2020, p. 1) They are currently under indictment for computer crimes related to the disruption of the 2017 French elections and the 2018 Winter Olympic Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea, and causing roughly one billion USD in damages to computer systems impacted by their malware.

The accuracy of attribution becomes exponentially more erroneous if the investigation is unable to reveal meaningful forensic evidence. When it comes to state-sponsored cybercrime, maintaining anonymity through operational security (OPSEC) occupies a large portion of the efforts within the campaign, and decreases the likelihood of retaliation. However, TAs have been known to intentionally leave behind evidence to confuse investigators, implicating other entities in the process. As van der Meer indicates, “traces can be wiped quite effectively, or even be manipulated, seemingly pointing to an innocent third party.” (2018, p. 2)

With this in mind, we must also consider the consequences that misplaced accusations can have on the sociopolitical environment. On average, government response to a cyber attack is usually far more reserved than that of rogue criminal groups and hacktivists. Allen & Demchak validate these concepts when they explain, “For a legal response, the identity of the perpetrator must be established. However, cyber-attacks are not launched frequently by a nation but by private citizens.” (2003, p. 57)

The Strategy of Response

Assigning a national identity to a threat actor is difficult, and for the private security industry, the practice is questionable. This is especially true when forensic evidence is elusive. But, there is more to attribution than enabling a proportionate political response. This is likely where the true motives behind any hastily made attribution can be found. Robert Axelrod and Benjamin Edwards have developed a framework for attribution strategy that can be defined as the following:“

[A] Bayesian game-theoretic model, in which the best strategic choice for the victim depends on the vulnerability of the attacker, the knowledge level of the victim, payoffs for different outcomes, and the beliefs of each player about their opponent.” (2017, p.1)

This model assigns a weighted value for each possible outcome of the attribution of blame, the dynamic of vulnerability, and the victim’s knowledge of the attack; and the results are surprising.

Using our scenario of Palestine (A) and Israel (B) we can use the model to perform a cost-benefit analysis. Considering A is not vulnerable there are two possible scenarios: increasing B’s attribution ability or decreasing A’s gain from an attack by increasing security. The outcome of this scenario is that neither option can prevent A from attacking. If A is vulnerable to blame, increasing public outcry by B will only increase the likelihood that A will attack in response. According to their model, “it is rarely beneficial for B to increase its own attribution ability” (Axelrod & Edwards, 2017, p. 9). It should be noted that the viewpoint of Palestine’s vulnerability is relative and that Israel is not responsible for the origin of the greater security industry’s Palestinian attribution of TA 402.

The nuances of assigning a Palestinian identity to TA 402 come to light upon Axelrod’s and Edwards’ observation that “If B is not knowledgeable, then it must play a strategy based on its prior beliefs about A’s type.” The evidence pointing to Palestine is minimal, unreliable, and inconsistent proving that the greater security industry is not knowledgeable about the identity of TA 402. Therefore, we can come to understand that the Palestinian theory may be influenced by bias, prejudice, marketability, or perhaps all three. The risk of political fallout from this is high and therefore unacceptable.

A Pound of Flesh

The potential impact of a response to a cyber attack from a government entity is clear. However, the response from a vigilante hacker seeking retribution has the potential to lead to more reckless and widespread damage. Between July 1999 and March 2002, hacktivists from Palestine, Israel, Lebanon, Germany, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Brazil, and the United States engaged in the defacement of 1,295 Israeli and Palestinian websites and subjected other sites to severe denial of service (DOS) attacks. Colonel Patrick D. Allen and Lieutenant Colonel Chris C. Demchack stated, “Broadcast servers that hackers used to launch attacks from one side were frequently used by the opposing side to launch a similar type of attack.” (2003, p. 2 ) in what would become known as the Palestinian-Israeli Hacker Conflict.

Again in 2011, “Arab-Israli tensions [began] spilling off the streets and airwaves and onto the regions fiber optic cables.” when hacktivists from Iran, Turkey, Lebanon, and Morocco targeted Israeli websites, defacing or disrupting service to more than 300 websites, including stock exchanges, airlines,

government services, and hospitals. (Clarke, 2012, p.A13) Additionally, hackers stole credit-card numbers and personally identifiable information and leaked them onto the internet.

The stability of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process can be characterized by the absence of hostilities between the two nations. This delicate balance could collapse due to the actions of a handful of provocateurs, leading to the disruption of commerce, government institutions, and telecommunication providers. Any turmoil that manifests in the socioeconomic system could lead to a political response that is perceived as unfair or unjust and escalate to violence.

Moving forward, the security industry can find great value in Axelrod’s and Edward’s models when considering the socio-political ramifications of attribution. Published work should only concern itself with identifying the nationality of a TA after a thorough cost-benefit analysis is performed. Doing otherwise is to risk becoming a tool of propaganda and calls into question the validity of the science.

The benefits of standardization within the industry can already be seen in the renowned MITRE ATT&CK framework. Identifying and tracking standardized tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) greatly enables defenders following an intrusion to remediate attacks by using this information to disrupt actions along the Cyber KillChain. Using this framework, professionals can triage security incidents based on predictable patterns. Agreeing on common naming conventions for attribution helps apply this framework without the impediment of translating the conventions of another organization.

Conclusion

Holding criminals responsible for their actions is a compulsory component of our pursuit of justice. A cyber attack can violate our privacy, financial security, sense of safety, and even our national sovereignty. It’s therefore understandable why governments go to such great efforts trying to discover the national identity of an attacker. However, assigning a national identity to an attacker by the private security industry is unnecessary and at times can escalate to plainly irresponsible. In many cases, attribution can influence public opinion and increase pressure on a government to respond to an attack. The responsibility falls on the private security industry to incorporate an ethical approach to attribution that includes the use of the Axelrod/Edwards framework, MITRE ATT&CK framework, and performing a cost-benefit analysis of the political consequences of making claims on national identity.

References

Allen, P. D., & Demchak, C. C. (2003). The Palestinian-Israeli Cyberwar. Military Review, 52–59.

Clarke, R. A. (2012, February 16). Cyber Attacks Can Spark Real Wars. The Wall Street Journal , pp. A

ClearSky Research Team. (2016, January 6). Operation DustySky. Clearskysec.com. Retrieved Novembe

15, 2022, from https://www.clearskysec.com/dustysky/

Dehghantanha, A., Choo, K.-K. R., Grooby, S., & Dargahi, T. (2019). Protecting IoT and ICS Platforms

Against Advanced Persistent Threat Actors: Analysis of APT1, Silent Chollima and Molerats. In

Handbook of Big Data and IOT Security (pp. 225–253). essay, Springer International Publishing.

Edwards, B., Furnas, A., Forrest, S., & Axelrod, R. (2017). Strategic aspects of`cyberattack, attribution,

and blame. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(11), 2825–2830.

Eruopol. (2016, December). ‘Avalanche’ network dismantled in International Cyber Operation. Europol.

Retrieved November 20, 2022, from

https://www.europol.europa.eu/media-press/newsroom/news/%E2%80%98avalanche%E2%80%99

-network-dismantled-in-international-cyber-operation

Fagerland, S. (2012, November). Systematic cyber attacks against Israeli and Palestinian targets going on

for a year. Oslo, Norway; Norman AS.

Greenberg, A. (2019, October 17). Inside olympic destroyer, the most deceptive hack in history. Wired.

Retrieved November 18, 2022, from

https://www.wired.com/story/untold-story-2018-olympics-destroyer-cyberattack/

14

Lemos, R. (2015, February 19). Middle East, North African Groups Learning Sophisticated Cyber-

Tactics. EWeek, 1. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from

https://web-s-ebscohost-com.ezproxy3.library.arizona.edu/ehost/deliver…

M. Amona, “Cyberwar emerges amid the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in Gaza,”h t t p : /

/cyberstrategies.wordpress.com/, Jan. 4, 2009;

http://cyberstrategies.wordpress.com/2009/01/14/cyberwar-emerges-amid-theisraeli-palestinian-con

flict-in-gaza/.

Marczak, W. R. (2017). Defending dissidents from Targeted Digital Surveillance (dissertation). ProQuest,

Ann Arbor, MI.

Romaniuk, S. N., Manjikian, M., & Cristiano, F. (2021). Palestinian territory occupied: cybersecurity at

reduced sovereignty. In Routledge companion to global cyber-security strategy (pp. 418–425).

essay, Routledge.

The Shadowserver Foundation. (2016, December 1). Avalanche – Law Enforcement take down.

Shadowserver. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from https://www.shadowserver.org/news/avalanche/

The Shadowserver Foundation (2022). [Unpublished raw data].

The United States Department of Justice. (2019, May 22). Goznym cyber-criminal network operating out

of Europe targeting American entities dismantled in international operation. The United States

Department of Justice. Retrieved November 20, 2022, from

https://www.justice.gov/usao-wdpa/pr/goznym-cyber-criminal-network-operating-out-europe-target

ing-american-entities

The United States Department of Justice (2022, July 13). Six Russian GRU officers charged in connection

with worldwide deployment of destructive malware and other disruptive actions in Cyberspace.

The United States Department of Justice. Retrieved November 17, 2022, from https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/six-russian-gru-officers-charged-connection-worldwide-deployment

-destructive-malware-and

Villeneuve, N., & Bennett, J. T. (2014, February 19). Xtremerat: Nuisance or threat? Mandiant. Retrieved

November 18, 2022, from https://www.mandiant.com/resources/blog/xtremerat-nuisance-or-threat

Winstanley, A. (2017, June 27). Hacker targeting Palestine Solidarity Campaign claimed to be Mossad.

The Electronic Intifada. Retrieved November 6, 2022, from

https://electronicintifada.net/blogs/asa-winstanley/hacker-targeting-palestine-solidarity-campaign-cl

aimed-be-mossad